I present, for consideration, this year’s GP A’ Level essay questions for the Singapore paper:

To what extent are science and technology able to solve the problem of waste disposal?

How desirable is it for a country to provide free healthcare for all its citizens?

Evaluate the measures taken in your society to deter crime and punish criminals.

‘Education today should involve more than the study of academic subjects.’ How far do you agree?

Assess the view that it is always right to challenge injustice.

‘Online advertisements use increasingly sophisticated methods to target consumers.’ To what extent does this bring more harm than good?

‘Humour is essential for an individual’s well-being.’ Discuss.

‘There is a lack of appreciation for the value of music.’ How far is this true in your society?

Paper 1 has always been the bane for many students; for those who have long graduated, it still haunts them like a phantom. Many of my past students tell me they hated the subject. I can see why: it’s extremely difficult to bring forth ideas into creation, what more for sheltered 17/18 year-olds who have largely only lived a singular narrative—not their own—their entire lives? To expect them to write an academic paper on global issues, and current affairs, where they are expected to understand and memorise examples, complex arguments, and multiple perspectives IS a tall order. If you ask me: a grown-ass, mid-life crisis-experiencing adult just trying to make his way in the world, it’s extremely difficult to be concerned about whatever’s happening outside my immediate vicinity. Unlike my more esteemed colleagues who take great pains to find out about so-and-so conflict or that law being passed which criminalises abortion, or whichever down-trodden marginalised group is injustice being heaped upon, a part of me strongly wants to turn inward and shut out the rest of the world—and I wager I’m not alone in this

Sometimes, adulting just means not wearing the same pairs of shoes on consecutive days to work.

Don’t get me wrong—knowing about the world around us IS an important skill, but it has to start from a position from somewhere. That is why the subject to me has always been archaeological—from the Greek, ‘arkhaios‘ and ‘arkhaiologia’ meaning the study of ancient things. The question I typically pose to students fresh to the subject is: how do I excavate parts of my previous seasonal self so that I can document and explain the changes happening to me and the world around me? After all, as much as Winter is (always) Coming, no two Winters are the same. This probably explains why many acolytes brute force the subject—and you can tell by the questions they ask:

how many paragraphs do I need to write to have balance?

how many examples do I need in one paragraph?

do I need to evaluate or 'contest’ each paragraph?

Again, these are important questions, but they are largely operational ones. A good essay relies largely on ‘proving’ the question, it’s more about ticking off a checklist—Aha! I have proven that science and technology can solve the problem of waste disposal because of ABC arguments and XYZ examples. How clever I am! In that sense, they aim to guide the reader to a pre-determined endpoint. Great essays, on the other hand, open up the discussion rather than narrowing it down. They interrogate the question and often end up asking more questions than they answer. Questions such as:

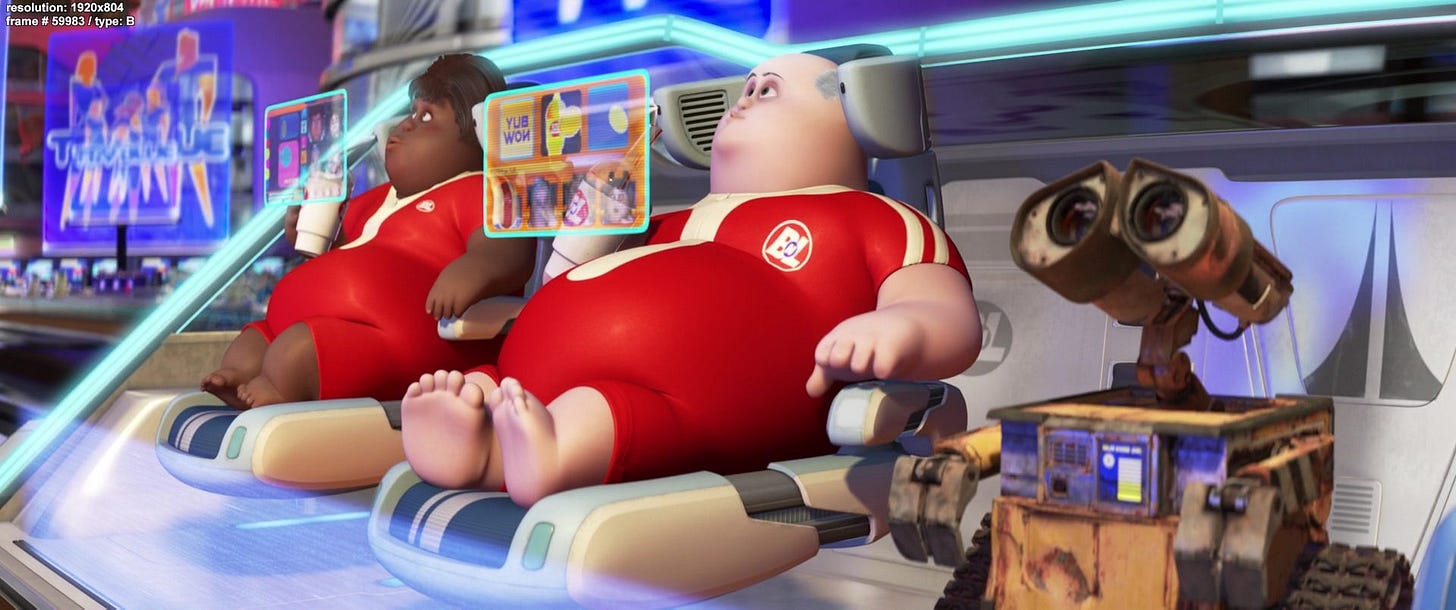

should we rely on technology to address waste management (like some Wall-E-esque future scenarios)?

what does it imply about the direction of a society that increasingly uses (and relies) on technology to address many of these problems

what is the human or societal cost of using such technologies—does it change our consumption habits, or how we organise our living spaces, for example?

A very real future ahead for us all, maybe on SpaceX branded mega-fleets. Hell, I already see this on Star Cruises.

If you notice a trend, each question’s demands are about being able to think of a context that exists beyond just some prepared examples and arguments. Many tutors—of whom I belong to and am guilty of—spend hours of lesson time going through, unpacking, distilling, breaking down the question, pick-your-choice of Analysis Verb—to provide argumentative handles for students to better understand the question demands. You have to pay attention to THIS Value Term; ‘Can’ does not imply ‘Should’; compare between the two terms; pay attention to ‘your society’, etc. Again, these are not wrong approaches, and to the students themselves, they are more likely to appreciate those methods. But I sometimes bristle (even at myself) when we mistake the subject’s form for its essence.

It is very easy to intellectualise many of these questions to simply be Big Picture Questions, but at the heart of each question is a very basic human concern—a hope, desire, or even a fear. Of course, free healthcare for all its citizens seems ideal—but in practice, does it ever work (c.f. the NHS)? Should Singapore go down that route of continually upping Eldercare/Shield for Old People who increasingly don’t contribute? Who bears the costs of all that medical treatment? Yes, humour is essential, but in this loneliness epidemic, is there even much to laugh about (which probably explains the Generation Alpha shift towards Absurdist humour)? Someone is asking these questions because they are real-world, lived concerns. The GP essay is primarily a test of maturity and how we understand our place in this lived world, and you simply cannot white-knuckle the two.

One of the assignments I typically give my JC2s to do during the June holiday period is an essay: ‘My life this year is better than before. Discuss.’ Part-skills exercise, part-autobiography, the essay is a convenient way for me to get to know them better; and I can roughly tell the ones who Understood the Assignment, and those who don’t understand even themselves. Just before they graduate, I try to return their essay and thank them for sharing their personal narratives. The mileage they take from this low-stakes activity tend to vary—but I like to scan the classroom for how they react and respond. I look out especially for the ones who—upon reading their own writing—cringe just that little bit. Unbeknownst to them, they have conducted archaeology even in a short span. And that little window of perspective is—to me—the start of a horizon of purpose.

Thank you for reading this far. Till then, keep being the brightest star for others.